Table of Contents

From European Thrones to a Mexican Hilltop

Chapultepec Castle, perched high above Mexico City, was once more than a monument to history—it was the stage of empire. While the castle has seen many uses throughout the centuries, one of its most fascinating chapters came during the 1860s, when it became the seat of imperial rule under the Second Mexican Empire.

The emperors of Chapultepec Castle were not many, but their presence marked a turning point in Mexico’s complex 19th-century struggle between monarchy and republic. This article explores who they were, how they came to rule, and how their legacy still echoes through the marble halls and elevated gardens of the castle.

The Road to Empire: Foreign Crowns in a New Republic

By the mid-19th century, Mexico was a young and unstable nation, rocked by civil wars, invasions, and economic hardship. Conservative Mexican elites, disillusioned with the republic, turned to Europe for support. They sought a monarch who could bring order—and international legitimacy—to the country.

In 1863, supported by French Emperor Napoleon III and Mexican conservatives, Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Habsburg was offered the crown as one of the Emperors of Chapultepec Castle. He accepted, and along with his wife Carlota of Belgium, arrived in Mexico in 1864 to establish the Second Mexican Empire.

Maximilian I of Mexico: The Idealist Emperor

Ferdinand Maximilian Joseph, better known as Emperor Maximilian I, was a younger brother of Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I. An intelligent and cultured man, Maximilian was more of a romantic than a realist—a fact that would ultimately contribute to his downfall.

After settling into Chapultepec Castle, Maximilian immediately began remodeling the residence to reflect his European sensibilities. With help from architects like Carl Gangolf Kayser and Julius Hofmann, and landscaper Wilhelm Knechtel, the castle was transformed into a neoclassical palace complete with a roof garden and imported European furnishings. The couple referred to the residence as Castillo de Miravalle.

Despite being installed by conservatives, Maximilian held surprisingly liberal views:

- He upheld land reforms initiated by Benito Juárez

- Defended indigenous rights

- Abolished child labor and debt servitude

- Promoted secular education

Unfortunately, his progressive ideals alienated many of his original supporters.

Empress Carlota: The Power Behind the Throne

Carlota of Belgium, daughter of King Leopold I, was not just a ceremonial empress. Intelligent, politically savvy, and deeply committed to the imperial project, she took an active role in administration and diplomacy.

Carlota was also instrumental in convincing Maximilian to accept the Mexican crown. She believed in the civilizing mission of monarchy and supported her husband’s reforms with vigor. During the final months of the empire, when French support began to wane, she sailed back to Europe to plead for help.

Her mental health deteriorated rapidly after being rejected by the Pope and various European courts. She never returned to Mexico and lived in seclusion for the rest of her life, dying in 1927.

The Fall of the Empire and Execution of Maximilian

With the end of the American Civil War in 1865, the United States began pressuring France to withdraw its troops from Mexico under the Monroe Doctrine. Napoleon III complied, leaving Maximilian without military support.

Despite multiple offers to abdicate, Maximilian refused. In 1867, his imperial army was defeated near Querétaro, and he was captured by republican forces under Benito Juárez.

On June 19, 1867, Maximilian was executed by firing squad—an event immortalized in Édouard Manet’s famous painting The Execution of Emperor Maximilian. His death marked the end of monarchy in Mexico.

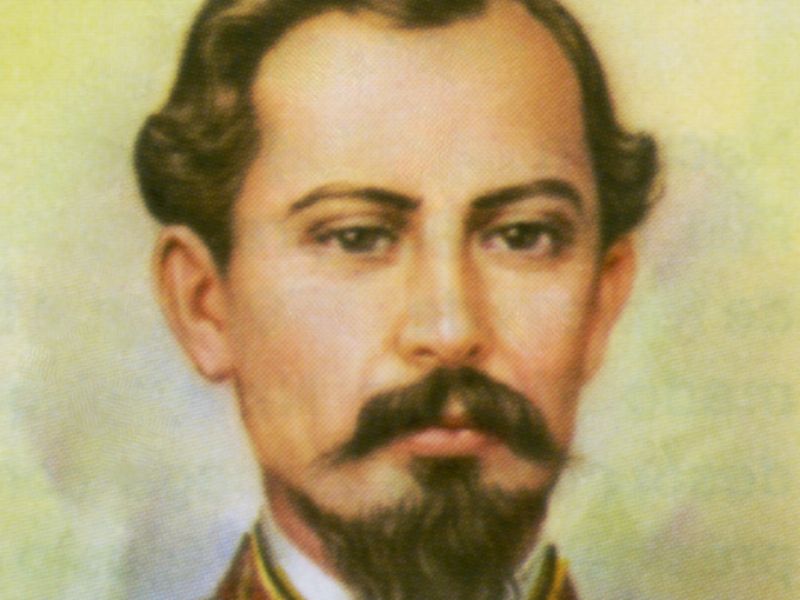

Miguel Miramón: The General-Turned-President Who Backed the Empire

While Maximilian was the only of the Emperors of Chapultepec Castle to reside, another prominent figure tied to the imperial era was Miguel Miramón, a Mexican general and former president who aligned himself with the Second Empire.

Miramón had previously served as President during the Reform War (1859–1860) on the conservative side. A graduate of the Military College located at Chapultepec, he knew the castle intimately and was deeply involved in its defense during various conflicts.

He was captured alongside Maximilian and executed in 1867. His story serves as a reminder of how personal ambition and political ideology collided during Mexico’s most turbulent years.

Legacy of the Emperors of Chapultepec Castle

The emperors of Chapultepec Castle left a legacy far greater than their short reigns. Their presence transformed the castle into a symbol of ambition, European influence, and tragic idealism.

The boulevard built to connect the castle to downtown Mexico City—Paseo de la Emperatriz, now Paseo de la Reforma—is still one of the city’s most important avenues.

The palace interiors, gardens, and preserved rooms of Maximilian and Carlota remain on display in the National Museum of History, offering visitors a direct connection to one of Mexico’s most dramatic political experiments.

A Royal Chapter in a Republican Nation

Though the empire fell, the echoes of the emperors of Chapultepec Castle still resonate. Their vision for Mexico was grand, idealistic, and doomed—but their impact on the castle, the park, and the country’s imagination remains deeply felt.

To stand in the castle’s alcázar, to walk its rooftop garden, is to walk in the footsteps of those who dreamed of a monarchy in a land already destined for revolution.